The Dirty Dozen of ‘W.W.W.’ military watches. Hear our take on the irresistibly collectible Dirty Dozen Watches. From Grana to Record, read more here…

From Hodinkee to Springbar, and Konrad Knirim to Z.M. Wesolowski, lots has been written about the horological ‘Dirty Dozen’ – 12 British military watches commissioned late in WW2. Successfully collecting all 12 originals has become one of horology’s most elusive challenges. After Geckota’s Tim Vaux met a collector with a full set of ‘D12’ watches, and one of the dozen came into his family’s possession, an article was inevitable…

In case this is your first stopping point on a journey into the world of The Dirty Dozen military watches, here’s the skinny on the irresistible, but elusive, 12…

A full set of Dirty Dozen watches - Image Credit: ACollectedMan

The rarity of complete sets of 12 original condition watches is clear from the fact that only around 20 complete sets are known to exist worldwide. Despite this, some of the group remain relatively accessible. Do you aspire to one example? Or do you have the budget (currently around £40k) to acquire all 12?

Either way, The Dirty Dozen appeals to many military watch collectors.

The irresistible collectability of watches exemplified

A full set of Dirty Dozen watches - Image Credit: Mike Mullaney

To understand The Dirty Dozen's appeal, you need only think about what makes watches so collectible – addictive, even. As the late American author and critic, Susan Sontag, wrote in 1992’s The Volcano Lover: ‘…the collector is a dissembler, someone whose joys are never unalloyed with anxiety. Because there is always more. Or something better. You must have it because it is one step toward an ideal completing of your collection. But this ideal completion for which every collector hungers is a delusive goal.’

This couldn’t be truer than for the 12 watches in The Dirty Dozen. You see, what initially looks like an achievable objective – to collect one each of 12 watches – is actually more complicated…

Focus on The Dirty Dozen

The Record Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

Let’s step back a moment from the infinite allure of an inexhaustible supply of new and pre-owned watches at every price point from a few pounds to millions. Focus instead on The Dirty Dozen – a veritable duodenary of timepieces brought together in an irresistible group. It’s a watch collection that initially looks equally accessible to super-collectors and those of more modest means. After all, with 145,000 watches made, how hard can it be to acquire one original example of each – particularly when a set of 12 originals shouldn’t cost more than, say, a new mid-range Mercedes?

Then again, maybe the reputed existence of only 20 complete sets of original watches indicates the challenge. But why so few?

The last months of WW2

Training for airfield defence: An Army instructor teaching men of the newly-formed RAF Aerodrome Defence Corps on the Thompson sub-machine gun at Whitley Bay, Northumberland, in January 1942. - Image Credit: MoD/Crown copyright 1942

To understand, let’s imagine ourselves back to the last months of WW2. In Europe, the Allies advance fast into Germany’s heartland, while, around the world, the end-game is on for Japan’s soon-to-be-defeated Southeast Asian empire.

Earlier in the war, 17 Swiss firms manufactured 133,600 British military watches under an older Army Trade Pattern (ATP) specification. Later, in 1945, the watches we call 'The Dirty Dozen' were commissioned.

An indelibly etched sobriquet

W.W.W. found on the Dirty Dozen - Image Credit: ACollectedMan

For nearly 20 years, they went under the descriptor “Watches, Wristlet, Waterproof" (W.W.W.). The identifier came from British War Office Specification R.S./Prov/4373A "Watches, Wristlet, Waterproof" (W.W.W.) for Service wristwatches. Then, in 1967, something happened that would eventually give the watches their sobriquet. Robert Aldrich’s now-classic war movie, The Dirty Dozen was released to massive commercial success. No association with the 12 watches was planned. However, their growing appeal to military watch collectors and WW2 connection means the ‘Dirty Dozen’ label later stuck fast.

The reason for their appeal?

So what are these 12 watches? And to what, apart from their wartime associations, does their appeal owe its origin? We’re not going to try to write the definitive online ‘Dirty Dozen’ article here. That probably exists already among a body of work on many esteemed watch websites. Not to forget Konrad Knirim’s acclaimed British Military Timepieces: Uhren der britischen Streitkräfte – the sister volume to his earlier Militäruhren. Instead, think of this as a jumping-off point to other works with some of our ideas thrown in – including, whether any of the group actually saw action.

The Dirty Dozen: fact and myth

The Record Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

Another clue to wartime service comes in a reference to an IWC archive extract confirming that an IWC Fliegeruhr, Mark X, was originally sold on February 21, 1945.

Thirdly, current Vertex Watch Company boss, Don Cochrane, says: ‘The very first of these timepieces were delivered late in 1944.’ In reality, few watches are likely to have seen the kind of action that characterised the movie. Earlier ATP watches are more likely to come with such provenance. They were stalwarts of British military timekeeping from the 1930s to 1943. That was when Commander Alan Brooke (later Field Marshal 1st Viscount Alanbrooke) realised the importance of having a purpose-made general-use military wristwatch – the first non-civilian watch specifically commissioned for the British military.

The elusive thirteenth…

A watch you'd expect to see from Enicar... - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

Of course, history and the group’s nickname would have been different with a thirteenth supplier … Apparently, alongside Büren, Eterna, Cyma, Grana, IWC, Lemania, Jaeger-LeCoultre (JLC), Longines, Omega, Timor, Record and Vertex, Enicar was also included. However, despite having an official store number, the company never supplied a ‘W.W.W.’ We can only guess why.

Just imagine what an Enicar would command if it was to surface…

What defines the ‘Dirty Dozen’?

The hands of the Record Dirty Dozen - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

The railroad of the Record Dirty Dozen - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

The traditional sub-dial of the Record Dirty Dozen - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

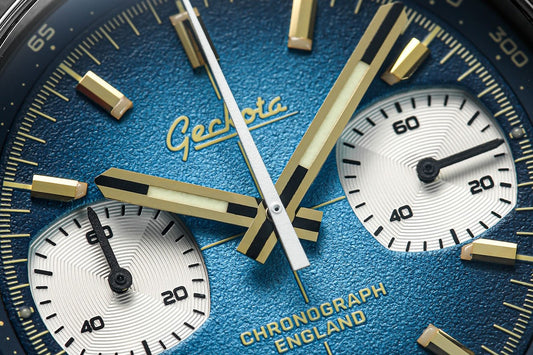

So back to the 12 brands that were part of 1945’s procurement. What a significant snapshot of 1940s watchmaking they represent, not least because several are no more. What then, was the procurement brief? If we could view Document R.S./Prov/4373A, “Watches, Wristlet, Waterproof” (W.W.W.), we’d see it was for a rugged water-resistant wristwatch with a stainless steel case. And a 15-jewel, hand-wind movement (between 11.75 and 13 lignes) with a Breguet overcoil balance. Each watch also had to be capable of chronometer-accuracy regulation. It also had to have high-legibility white Arabic characters on a black dial, luminous hands and indices, a ‘railroad’ minute track and sub-seconds at 6’o’clock. Add a shatterproof crystal, fixed lug bars, engraved British military Broad Arrow (‘Pheon’), a similarly marked ‘W.W.W.’ abbreviation and a military serial number.

The watches came on a calfskin strap or hand-sewn A.F.0210, ’44 pattern’ webbing strap.

Collectability assured

The Record Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

On this foundation, though the last thing on minds in 1945, the 12 watches’ future collectability was being ensured. Then things got even more complicated and the watches’ appeal was further enhanced. That’s because, within the framework of a standardised specification, brand-specific variations crept in. Since then, lack of concern for maintaining ‘originality’, central servicing by the Royal Electrical & Mechanical Engineers (REME), and 1970s concerns about lume radioactivity have only increased scarcity.

So did varying manufacturing volumes. And the way only Omega, Jaeger-LeCoultre, and IWC kept accurate production records. For the Omega, Cyma and Record watches, production approached 25,000. For others, the volumes were much lower. The rarest (unless someone has an Enicar) is the Grana, with fewer than 1,500 made.

The Record Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

Nevertheless, ‘Dirty Dozen’ watches remain affordable, with good examples ranging from a few hundred pounds to five figures, depending on the model and its condition. The varying production runs, plus regular cannibalisation in military workshops, only makes originals – without ‘REME hands’ or mismatched case backs – harder to find.

That’s why, over 75 years after delivery, so few sets of 12 original watches have been assembled. And why, though individual watches aren’t generally as highly prized as other military watches, the allure of a full set is undiminished…

Interbrand variations

The Buren Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: Mike Mullaney

From the moment the procurement brief was interpreted by the manufacturers, other appealing variations found their way into the 12 watches. Look closely at the ‘Dirty Dozen’ and you’ll soon notice these.

A Cyma Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: ACollectedMan

The rarest of them all, a Grana Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: ACollectedMan

Maybe it’s the ‘hungry’ sub-seconds on the Büren, Eterna, Grana, Lemania, Omega and Vertex, or the Longines’ cathedral hands and stepped ‘Tre Tache’ (‘three notch’) case. Or perhaps the IWC’s – unique among ‘W.W.W.’ watches – snap-back case that appeals. Or the JLC’s gilt-finished Calibre 479 movement. Other ex-works variations encompass case diameters, which range from 35mm to the Longines’ ‘almost contemporary’ 38mm.

The IWC movement found in the Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: ACollectedMan

Suddenly, you realise that what initially looks like a simple collector’s grail of 12 watches is anything but. If you just want one example, your challenge is easier than building a full collection. You choose among the brands, search, then assess the authenticity of possible purchases before buying. Will it be a relatively common Record or that rare-as-hens-teeth Grana (only a handful sold since 2012)? The dream is yours, though realising it may prove harder with some brands than others.

A Timor Dirty Dozen watch -Image Credit: Mike Mullaney

Unfortunately, reverting to the inherent addictiveness of watches and pursuit of Gestalt – an organised whole perceived as more than the sum of its parts – means a complete set will remain a tempting objective for many.

Now things become much more complicated. First, there’s the decision about your first ‘Dirty Dozen’ watch – which may or may not be determined by the first good example you find. Then come decisions about going for a ‘representative’ set – albeit with some ‘REME’ hands and case backs – or a set of original, unadulterated watches. Even then, more decisions await, not least whether to include (or add) variants created by the disposal of some ‘D12’ watches to other armed forces, such as those of the Netherlands, Royal Netherlands East Indies (Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indische Leger or KNIL) and Army of the Republic of Indonesia (ADRI). With only a handful of documented examples, these may be the rarest of the rare…

The Record Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

The rarest of them all, a Grana Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: Mike Mullaney

In this case, the objective was just the one example. However, at the other end of the collecting spectrum there’s always the allure of that incredibly hard-to-complete set of 12 authentic, original watches. As Tim Vaux knows from a recently viewed collection, even years’ painstaking acquisition can still leave collectors tantalisingly unfulfilled – in this case, because the Longines ‘W.W.W’ wasn’t 100% original, as-issued…

Is this the ultimate military watch torment, or a lovely problem to have? After all, the Longines, though among the rarer ‘D12s’ (with an estimated 5,000 to 8,000 examples), is likely to be easier to replace with a better example than a Grana!

A beautiful Longines Dirty Dozen - Image Credit: Mike Mullaney

In many collectors’ eyes, it’s the Grana, Longines, Omega, IWC and JLC that hold greatest appeal. In the Geckota office the Longines (‘size, brand and stepped case’) and Omega (‘it’s a classic Omega’) top desirability alongside the ‘very cool’ IWC and uncommon – ‘who wouldn’t want one for rarity alone?’– Grana. Talking ‘Dirty Dozen’ watches inevitably leads to their legacy and influence on later watches. Given that the 1944 Ministry of Supply brief pretty much re-defined the basic simple, rugged, tactical watch, this debate rarely ends definitively.

Arguably, almost any similarly specified watch from the late 1940s until today could be deemed to be ‘influenced’ by the ‘W.W.W.’ Or by comparable military watches emerging from other Allied (the ubiquitous A-11 ‘wristwatch that won World War 2’) and Axis powers. Just look at The Dirty Dozen, then your favourite watch websites, books or catalogues, to spot their design language in generations of watches.

We love the case on this IWC Dirty Dozen piece - Image Credit: ACollectedMan

Likenesses abound, from 1950s Bulova 10 AKs and Soviet Pobedas, through 1960s Jaquet-Droz timepieces and the Hamilton 6b, to modern watches such as the Seiko SNZG15 and Timex TW2R46500. So far, there’s no direct ‘D12’ influence in Geckota’s product family. ‘But,’ says Tim Vaux, ‘it’s one of many influences that could help determine future Geckota watches.’ Much easier to identify are a few modern watches with direct bloodlines and explicit branding links back to the ‘Dirty Dozen’. For practical purposes, Büren, Grana, Lemania, Timor and Record are long gone. A copy of The Essence of Omega that I picked up at Baselworld 2018 contains nothing remotely like – yet alone descended from – Omega’s 1945 ‘W.W.W’. Eterna’s 2016 range catalogue offers their limited edition ‘1939 Military’. With its simple three-handed design and railtrack seconds it alludes to the ‘Dirty Dozen’ – if you overlook the tonneau case and missing sub-seconds.

The JLC Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: Mike Mullaney

Equally, despite the Jaeger-LeCoultre being another ‘W.W.W.’ favourite (case quality, over-finished movement and cathedral hands), JLC’s 2018-19 brochure relies not on historical reference to WW2 but on its new Polaris collection as it appeals to ‘men of action’.

For three of the dozen (the Longines, IWC and Vertex) the bloodline continues much more explicitly. Notwithstanding debate about whether the Longines accompanied 1952’s British Northern Greenland Expedition, the Longines 'Dirty Dozen' British military - F 4724’ has clearly inspired later Longines Heritage watches. These include an explicit ‘W.W.W.’ facsimile, the brand’s Military COSD timepiece, 2016’s Heritage 1945 and Military Heritage watches.

IWC does even better: the IWC Mk X is the only ‘Dirty Dozen’ watch that’s part of an ongoing series. Okay, so today’s ‘IWC Mk’ watch is the Mark XVIII Edition “Tribute to Mark XI’. Nevertheless, the lineage goes back directly to the legendary IWC Calibre 83 movement inside 1945’s ‘Watch, Wristlet, Waterproof’. And so to the third ‘D12’ watch that has close, authentic connections with a modern watch.

The Record Dirty Dozen watch - Image Credit: WatchGecko Online Magazine

If this is your first step to learning more about these collectible military watches, do read the websites and books that we’ve referenced. Then, whether you’re just curious, want to own one example, or aspire to a full collection of 12 originals, make sure you enjoy the journey. And do stop by to tell us how the pursuit of your Dirty Dozen is going!