Pilot chronographs - in the air it's all about time. Read on to find out what makes pilot chronographs among the best aviation watches available...

Pilot chronographs - In the air, it's all about time

Part 1: So what is a pilot chronograph?

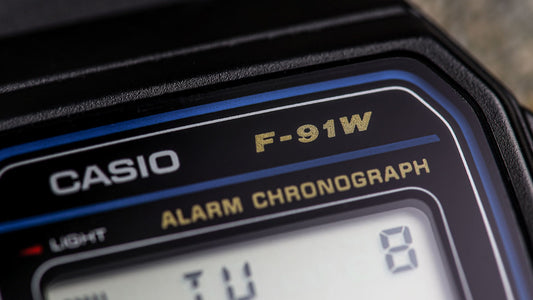

Technology's progress inevitably means that for many people, traditional watches are being replaced by computerised electronic devices - mobile phones, smartphones and smartwatches such as the Apple Watch. Yet hand in hand with technology's relentless march, there's been a resurgence of interest in traditional watches. If you're reading this, the likelihood is that you can identify with the appeal of wearing traditional analogue timepieces - whether quartz powered or mechanical. We've seen it with divers' watches (now usually replaced by dive computers) and racing chronographs (replaced by sophisticated electronic timing). In addition, we've seen it with pilots' watches including pilot chronographs.

In the air, it's all about time: estimated time of arrival (ETA); points of no return, time to fuel exhaustion; time to missed approach; time to drop bombs or release today's terrifying smart weapons; and more'¦ So let's push the metaphorical yoke forwards and dive into the world of pilot chronographs, that most important subset of pilots' watches, and arguably the quintessential aviation watches.

The perennial appeal of chronographs

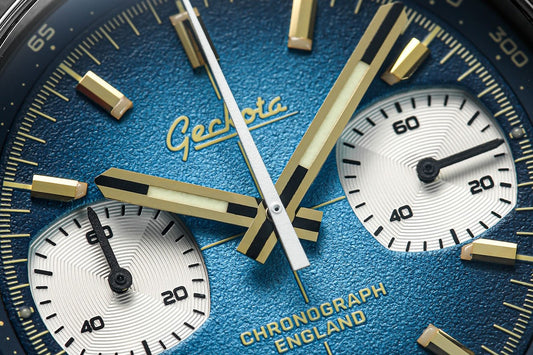

While introducing a recent issue of QP magazine, Timothy Bamber asked, '˜What is it that makes [the chronograph] such a perennially appealing, nay essential, watch so long after the tasks for which it was designed became redundant?' Continuing, Bamber suggests that a chronograph isn't just a watch to look at, but one to interact with as it satisfies its '˜techy, toolish' audience. Could he mean pilots or wannabe pilots, or even those who are simply fascinated by aviation? Is the reason for their enduring fascination, he postulates, '˜the pleasingly busy look of sub-dials, registers or scales - their meanings now utterly arcane - crowded onto the dial'? Ironically, there's a fundamental conflict between what constitutes a true '˜aviation watch' or a '˜watch for aviation' and the pilot watches that have come to define a whole sub-category of timepieces. Among these, whether sub- £100/$100 quartz watches or astronomically priced COSC-certified aviation chronographs from ultra-luxury manufacturers are pilot watches that are also pilot chronographs - arguably the highest of high-flying wrist instruments. Here's another paradox. Given pilot watches' traditional definition by accuracy and readability under all lighting conditions, it's interesting how many (particularly feature-laden pilot chronographs) are among the hardest to read and use as intended. Some commentators go so far as saying that aviation-related features on pilot chronographs are essentially unusable for serious aviation. More later, but first, what is a chronograph in general, and a '˜pilot chronograph' in particular?So what is a chronograph?

In short, the chronograph (literally '˜time writer') is one of the most complex, sophisticated (or '˜difficult' as the horologists say) watch complications that man has devised. '˜A chronograph - or more correctly "chronoscope" - is a watch with an hour hand, a minute-hand, and a special additional mechanism which, at a push of a button, alternately starts a (usually) centrally positioned elapsed-seconds hand, stops it, and returns it to its zero position. The ordinary time display remains unaffected. Even cursory examination of the watch market reveals that most affordable chronograph watches are powered by quartz movements - if you are considering pilot watches under £1000 and want an aviation chronograph, it probably won't be a self-winder. This reflects the high cost of creating quality automatic chronographs. There are a few exceptions in the form of cheap chronograph watches powered by Chinese movements, including watches by Ingersoll 1892 and hand-wound Seagull chronographs such as the Seagull 1963, which recreates a watch developed for China's air force in the 1960s.What is a 'pilot chronograph'?

So, assuming for the moment that pilots actually do wear watches for functional purposes - as they did in the first half of the twentieth century - what constitutes a pilot's chronograph? Just as unidirectional bezels and Helium release valves have insinuated themselves into dive watch culture, certain features have a similar role in pilot watches - and in particular, pilot chronographs.A fully featured pilot chronograph

Based on conventional wisdom, we reckon a fully featured '˜dream' pilot's chronograph would have the following characteristics - the characteristics of a basic pilot's watch with chronograph and other functions added:- Accuracy.

- Easy readability in adverse conditions (particularly low light).

- Elapsed-time stopwatch for up to 12 hours.

- Flyback function for instant zeroing and restarting without having to press stop and restart pushers.

- A double-stop function with rattrapante ('catch up') capability.

- Antimagnetic properties.

- A rotary slide rule for flight related calculations.

- A tachymeter (or tachymetre) scale.

- Hacking capability (for synchronising several watches, particularly for military use).

- Dual-time capability to display local and UTC (Universal Coordinated Time).

Accuracy

If a watch works within generally accepted accuracy standards, it's sufficiently accurate for civilian aviation, and probably many military uses. Airline pilot and author, Patrick Smith sums the situation up perfectly when he writes about the place of wristwatches in modern aviation: The purpose of the watches is to tell us what time it is. Watches are required as backups to the ship's clocks, but nothing more elaborate than a sweep hand is needed.

Easy readability

As discussed in our earlier article on Fliegeruhren, most of the original pilots' watches, as exemplified by timepieces such as IWC's 1940 Big Pilot watch, featured highly legible, well-lumed, hands, numerals and indices - typically light-coloured for high contrast against a simple dark dial.Elapsed-time stopwatch function for up to 12 hours

In the halcyon days when dead reckoning air navigation was the norm, it was necessary to have a record of the elapsed time along a chosen course. The term dead reckoning comes from DEDuced Reckoning, a form of navigation known to mariners for thousands of years that involves plotting an aircraft's position by calculations of speed, course, time, effects of wind, and previous known position. It's a basic skill that's still taught to aviators in our age of high-technology navigation aids - and it requires an accurate clock or watch.Flyback capability

Flyback functionality (also called '˜retour-en-vol' or '˜instant restart') has an important military aviation role and enables a pilot to read the times for two consecutive events quickly without having to press two buttons several times.Rattrepante double stopwatch complication

The word '˜rattrapante' comes from the French word '˜rattraper', which means '˜to catch up with'. A rattrapente complication uses two sweep hands. When the stopwatch function is initiated, both hands rotate together; when the Stop button is pressed, one of the two hands stops, but the second continues until it too is stopped. Thus, two sequential times can be recorded.

Antimagnetic properties

From the earliest days of putting watches into aircraft cockpits, watchmakers were challenged to protect their precision movements from the effects of magnetism created by aircraft, initially with iron shielding and more recently with sdvanced non-magnetic materials for the mainspring.Rotary slide rule

The rotary slide rule on many pilot chronographs harks back to the days before widespread availability of electronic calculators, smartphones and other modern calculation devices. Based on the E6-B flight computer, a rotary slide rule enables various flight related and general calculations. Be warned though, it's fiddly!Tachymeter (or 'Tachymetre') scale.

This is another scale often associated with chronographs - a function for calculating speed (based on travel time) or distance based on speed. It's simply a way to convert elapsed time into speed (in units per hour) - in the case of aircraft, into ground speed.Hacking complication (also 'stop-second')

This refers to being able to stop a watch's seconds hand by pulling the crown out to the time-setting position. This enables the watch to be set precisely against a time signal or synchronised with a reference watch.

Dual-time capability

As Ryan Schmidt explains in The Wristwatch Handbook, when the wristwatch was conceived, there was not a great deal of global travel, nor was the world strung together by cables, satellites and cell towers. How communications, aviation and watches have changed since then. Following the rise in long-distance rail travel in the 1850s, the 1884's International Meridian Convention established the prime meridian at Greenwich. And with it, the adoption of the 24-hour global time zone concept that we take for granted today. Later, growth of international air travel in the 1940s and 1950s increased the requirement for pilots and travellers to tell the time across one or more international time zones. Thus was born the dual-time function with its characteristic 24-hour hand (and on some watches a 24-hour bezel too) - as epitomised by the Breitling Chronomat GMT chronograph.Evolution of the pilot's chronograph

With the development of military and civilian aircraft around the time of WW1, aircraft cockpits started evolving into the instrument-packed areas that we know today. Although existing as pocket watches since Louis Moinet invented the first chronograph, it was only in the 1930s that wristwatch chronographs, and in particular pilot chronographs, achieved any kind of maturity. This was the decade when manufacturers such as Hanhart, Junghans, A. Lange & Söhne, Tutima, IWC, Hamilton, Omega and others made the best pilot watches of the time for the Allied and Axis forces. Until then, man was too busy adapting pocket watches to the wrist, working out how to protect watches and their wearers from the rigours of war, and applying basic watch technology to navigation on land, sea and in the air. Not surprisingly, military and government use, first for WW2 and later during the Cold War, followed by the growth of international air travel, gave impetus to civilian adoption of chronographs.The need for watches for flight calculations is gone

Nowadays, with a wealth of advanced timekeeping and navigational equipment in the cockpits of all but the smallest planes, and sophisticated navigational calculators, the need for pilots to use wristwatches for flight calculations has gone. It's been more than a while since they were either useful, or necessary for celestial navigation, timing bomb-runs, counting down engine checks or the other timed tasks associated with aviation. Today's commercial and private pilots often fly with an independent timepiece for safety back up in the (nowadays highly unlikely) event of total systems failures. However, as we'll see later, the main reason for pilots to wear watches nowadays is the same as for the rest of us - to tell the time. Even allowing for the different requirements of large commercial aircraft and small general aviation planes, and for the differences between civilian and military flying, if one complication stands out as being useful for modern pilots, it's probably a dual-time function rather than the chronograph, flyback or miniature rotary slide rule.Classification of chronographs

There are various ways to make a 'quick and dirty' chronograph taxonomy: main use; design; type of chronograph mechanism; or a combination of the three.

Main use of the chronograph

To start with application, the following have all appeared:- (Motor) racing chronographs

- Production-counting chronographs

- Phone-call timing chronographs

- Tide register chronographs

- Pilot chronographs

Number of pushers

Another way is by the number of buttons (or 'pushers') for operating the chronograph function:- Single-button pusher

- Double-button pusher

Chronograph functions

Then there's classification by chronograph functions:- Chronograph with hour counter

- Split-second chronograph

- Chronostop function

- World-time function

- Calculator function

- Tachymeter function

- Telemeter function

Coupling the chronograph and base movement

Classification of chronographs and pilot chronographs can also be done based on how the chronograph and base movement are coupled:- Classic horizontal wheel coupling.

- Oscillating pinion.

- High-end vertical friction clutch.

- Other mechanisms, such as Alpina's proprietary 'swivelling component' with two toothed pinions.

Mechanical execution of the chronograph function

Then there's classification based on mechanical execution of the chronograph function when the 'pushers' are pressed:- Castellated column wheel (crown wheel) coupling

- Cam/lever actuation

Number and type of sub-dial

Yet another (albeit rather simplistic) way to classify chronometers is by the number and arrangement of sub-dials. However, be warned that this can lead into ambiguity... Chronograph watches typically have two or three sub-dials:- One for chronograph minutes (30, 45 or 60).

- One for chronograph hours (12 or 24).

- A third for running seconds (often centrally, for clarity).

Evolution of Universal Geneve's Compax

Over the next 50 years, Universal Geneve's Compax evolved into a many derivatives, including 'Aero-Compax' watches for airline pilots (from 1940) and the very rare Aeronautica Militare Italiane Cronometro Tipo CP-2 with its 'retour en vol' (return in flight) instantaneous flyback and large ball-shaped crown for easy operation while wearing flying gloves. Think of pilot chronographs today and it's probably Breitling, Omega, Rolex, IWC and others at the forefront of modern aviation chronography that come to mind. But please remember the one-time importance - dare we say leadership - of Universal Geneve in chronographs. For many chronograph enthusiasts (to the frustration of Universal Geneve aficionados), the idea of '˜Compax', Uni-Compax and '˜Tri-Compax' is often incorrectly applied to the number of sub-dials, rather than the number of complications over and above the basic running seconds function. This regularly leads to forum questions such as why '˜Tri-Compax' chronographs have four auxiliary sub-dials - the answer being that one dial is a moonphase complication.

Two sub-dials does not a true '˜bi-compax' make

Equally frustrating for UG fans is the nomenclatural 'reverse engineering' that's led to chronographs with two sub-dials (similar to Universal's original Uni-Compax configuration) being widely referred to as 'bi-compaxes'. According to Ryan Schmidt's The Wristwatch Handbook, this is due to 'a misunderstanding of the 'uni' and 'tri' prefixes' Nevertheless the term has stuck. (Just to add further confusion, the term 'Compur' was also used for some Universal Geneve chronographs with two sub-dials) Classify chronometers by the number of sub-dials if you must. However, while you do so, please remember the true meaning of 'compax' as originally defined by Universal Geneve in its heyday.

Iconic pilot chronograph brands

This is where things may get controversial. In researching this two-part article, we've tried to identify some of the most significant and interesting examples of pilot chronographs. We've deliberately concentrated on the historical evolution of this watch category, so some newer brands, such as Bremont and Christopher Ward, will have to await a future article. What's more, we realise that someone's favourite watch will have been omitted. It's inevitable when we've had to compress over 100 years of pilot chronographs into a few thousand words. If we've omitted your favourite, or something important about a brand we've mentioned, please tell us. Now to the watches:Cartier

Though still not a major name in chronographs, let alone pilot chronographs (Cartier didn't have an in-house chronograph movement until 2010), the Paris-based jeweller's 1904 'Santos' watch (in series production from 1911) is so significant for aviation watches that it deserves mention. Besides, the evolution of the pilot chronograph goes hand in hand with the development of aviation watches - and aviation itself. Cartier's involvement began in Belle Epoque Paris when Louis Cartier's friend, pioneering Brazilian aviator and bonne vivant Alberto Santos-Dumant, complained about problems he was having with his pocket watch. In particular, the difficulty of telling the time and checking flight times on a pocket watch while using his hands to control his flying machines. As a result, Cartier worked with horological technician Edmond Jaeger to develop an aviation wristwatch for Santos-Dumont - with Roman numerals, two hands, a large crown and a leather strap. The first 'Cartier pilot watch' wasn't a chronograph and it wasn't a chronometer as we know it today. And it didn't have the round dial that became the norm for pilot chronographs in two world wars. However, as Gisbert L. Brunner and Christian Pfeiffer-Belli say about the 1911 'Santos' in The Watch Book, 'Louis Cartier emancipated the styling of this new star in the watch heavens.' With the first Cartier pilot watch, the aviation watch had literally and figuratively taken off.

Breitling

If there's one brand whose aviation pedigree is front of mind in the popular consciousness, it's probably Breitling. The company was founded by Leon Breitling in 1884 and is now promoted with the '˜Instruments for Professionals' tagline. From the start, Breitling created counter chronographs and measuring tools that caught the attention of Switzerland's watch industry. Breitling, which has always focused on measuring brief intervals of time, has enjoyed a long, close relationship with aviation and chronographs. It's no surprise then, that their pilot chronographs are among the world's best known.The archetypal pilot's watch?

For one of the companies with the strongest claim to make the archetypal pilot's watch, Breitling has come a long way from inventing the first single-button chronograph in 1915. They patented the first double pusher in 1934, a chronograph for aircraft cockpits in 1936, the 1941 Chronomat (based on a 1940 patent for 'an instrument-style wristwatch with a circular slide rule') and the iconic 1952 Navitimer that evolved from the Chronomat. In 1969, with their Caliber 11 '˜Navitimer Chrono-Matic' Breitling was a pioneer of self-winding chronographs. The so-called '˜Project 99' was developed with Hamilton-Buren, Heuer-Leonidas and Dubois Depraz, and powered by Buren's proven microtor movement. This was the only self-winding calibre available at the time that would allow the rearward, servicing-friendly, installation of the specially developed chronograph module. Less than a decade later, at the height of the Quartz Crisis, Breitling changed hands, relocated and went on to even greater success - arguably starting with 1980's Breitling Jupiter and Breitling Jupiter Pilot. With so many achievements behind them, one hurdle remained as some chronograph fans still criticised Breitling for being '˜just a high-price ETA case maker'. At least, they did until the launch of Breitling's first in-house, series-produced, COSC-certified chronograph movement at Baselworld 2009. The timing, befitting a precision chronometer manufacturer, was perfect. The announcement of the automatic B01 movement, with its column-wheel chronograph and vertical coupling, coincided with the 125th anniversary of Breitling's foundation. An important new Breitling pilot watch had been born.The defining Breitling design

Though lacking the later in-house movement, 1952's Navitimer is arguably the definitive Breitling design. And the most iconic Breitling pilot timepiece. But not in everyone's book as neither the Navitimer nor Breitling are mentioned in the Design Museum's Fifty Watches That Changed the World. However, March 2013's A Blog to Watch feature placed the Navitimer eighth in the twentieth century's top 10 classic watches (after the Rolex Submariner, Omega Speedmaster chronograph, Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, Jaeger LeCoultre Reverso, Rolex Datajust, Heuer Monaco chronograph and Glasshütte's Senator Navigator). A similar feature (Issue 74 of luxury watch magazine QP) put the Navitimer among the world's greatest chronographs (at least 25 years old, pre Quartz Crisis and with a damned good story to tell). The magazine added revealing commentary. For instance, the Navitimer is the oldest Swiss mechanical chronograph still in production and its fundamentals are consistent with those of the 1952 original. What's more, according to the magazine, the fact that it has been copied so often '˜is a clear indication of just how good a piece of design it is.'Popularity with 'wannabe flyboys'

Unfortunately, despite being so highly rated, the pros are countered by the Navitimer's '˜unfortunate popularity with wannabe flyboys, it's a bit too fussy it's so specifically a tool watch [and] as a pure expression of what a chronograph should be, it's let down by being able to do too much.' Since 1952, the Navitimer has spawned numerous derivatives, including special limited editions and the Navitimer GMT. The latter with what is probably the most useful complication for modern commercial pilots - dual-time capability. The Navitimer is arguably the quintessential pilot's chronograph with its rotary aviation slide rule built into its rotating bezel for navigation and other flight calculations. According to Breitling, this '˜has since become a cult object for all dedicated aeronautical enthusiasts'.An '˜authentic instrument panel on the wrist'

To quote Breitling's own publicity, it's '˜an authentic instrument panel on the wrist. Undoubtedly, Breitling's aviation pedigree was only enhanced by Breitling HUIT Aviation's role as a supplier of cockpit chronographs to the RAF during WW2. And the creation of specialist wrist chronographs for wartime pilots. Later, with the jet age, Breitling, and Wakmann, supplied cockpit instrumentation for aircraft makers such as Boeing (707), Douglas (DC-8), Lockheed, Sud Aviation (Caravelle) and Vickers. Contemporary advertising used the '˜Breitling time for the plane for the pilot' headline. And as a BOAC supplier in the 1950s, Breitling even had a watch aboard the first civilian jet airliner, the Comet, when it flew to South Africa. Furthermore, the Navitimer was soon adopted as official timepiece of the international Aircraft Owners' and Pilots' Association (AOPA). One of the most interesting Navitimer stories, and a clue to the watch's collectability, is in Wesolowski's A Concise Guide to Military Timepieces. The story concerns a large bag of confiscated Iraqi-marked Navitimers that turned up in Tehran just after the start of Gulf War I. Check out the (excellent) book to read more'¦ Since then, a whole suite of Breitling chronographs has evolved to include the aforementioned B01, Navitimer evolutions, Chronoliner, Chronomat and '˜globe faced' Transocean Unitime.Into space

With the space race came the Navitimer Cosmonaute, as worn by NASA astronaut Scott Carpenter. Omega's Speedmaster may be the '˜Moonwatch', but in 1962, as Carpenter orbited earth in Aurora 7, the Cosmonaute was the first wrist-worn chronograph in space. Breitling maintains many hands-on aviation links, not least through involvement with air racing, display flying and themed chronographs. As well as their own air display teams, they collaborated with the RAF Red Arrows between 1966 and 1996. In addition, in 1983, Breitling developed the Chronomat with Italy's Frecce Tricolori aerobatics team. Breitling is also the official worldwide partner of the World Air Sports Federation (FAI) and supplies the FAI's official watch. Breitling is also prominent in aerial exploration and record breaking, including the world's first balloon circumnavigation in 1999 by Brian Jones, Bertrand Piccard and Breitling Orbiter 3. Other high-profile brand ambassadors include actor-pilot John Travolta. Breitling also operates a promotional aircraft fleet including classic twin-prop DC-3 and four-engined Lockheed Constellation airliners.Breguet

Abraham-Louis Breguet, born in Neuchatel in 1747, was arguably the most important watchmaker ever. His business also went on to be one of the iconic Post-WW2 pilot chronograph suppliers. Some 200 years after Breguet started his business, the 1950s saw the launch of the most famous Breguet pilot watch, the Type XX. With this timepiece, Breguet, adding to everything else achieved over two centuries, was thrust into the firmament of great military watches alongside the likes of IWC's legendary Mark 11 or Panerai's Radiomir 1940.Genuine military DNA

The Type 20 flyback chronograph (actually made by Mathey-Tissot) gave Breguet genuine military DNA. The company has carried this into the latest Type XX (now Type XX Aeronavale), XX1 and XXII chronographs tucked away at the back of brochures packed with Classique Grandes Complications and Reine de Naples collections. From 1950, many air forces equipped aircraft with chronographs based on Breguet's Type X1 wristwatch. Breguet also supplied pilots' pocket watches. Starting in 1954, Breguet supplied the Type 20 '˜dead reckoning' chronograph (along with Auricoste, Dodane and Vixa) to France's Armee de l'Air, Aeronavale (equivalent to the RAF Fleet Air Arm) and Centre d'Essais en Vol (test facility). Other air forces, including Morocco and Argentina's, also issued Type 20s. There's a must-read article about the latest Type XX1 Breguet pilot timepiece and its illustrious predecessors in Issue 79 of QP magazine. In the article, Timothy Barber explains how the Type 20's flyback function was important for the dead reckoning navigation that predominated in French military aviation. This contrasts with the RAF's focus on celestial navigation at the time. But that's another story, for later.

TAG Heuer

In The Watch Book II, Gisbert Brunner says: '˜The chronograph runs like Ariadne's thread through the lives of Edouard Heuer and his successors.' For many people, TAG Heuer (previously Heuer and Leonidas-Heuer) and its chronographs are most strongly associated with equestrian sports, skiing, athletics and motor sport timing. However, history has given us some impressive TAG Heuer pilot chronographs too. These included watches such as the 1970s '˜Bund Heuer' and the Heuer Pilot (a '˜true Heuer', given its development well before the company's sale in 1982) from the 1980s and 1990s '˜Specialist' range. As Martin Häussermann starts his TAG Heuer chapter in Sports Watches, few other watch brands stand for sports like TAG Heuer. But Heuer - and later TAG Heuer - was most closely linked to motor sports.' The importance of this automotive connection is unarguable, but dig deeper and it's clear that the company has also played its part in aviation timekeeping. The TAG Heuer pilots' watch may be a rare beast these days, but the brand has created some important aviator watches in its time. That's hardly surprising, given Heuer's lifelong specialisation in timekeeping and chronographs - and timekeeping's importance for aviation. Not long after its formation, Heuer created its first pilot's watch, with large hands and dial for '˜optimal legibility' in early cockpits. In 1911 came the patented 110 mm-diameter '˜Time of Trip' dashboard chronograph for car and aircraft cockpits - including those of the R34 airship (first Atlantic crossing in 1911) and the Graf Zeppelin that circumnavigated the world in 1929. Soon after, Heuer consolidated its reputation with the world's first 1/100th second chronograph.